Caves are environments, not dioramas. People walked through them, and they were used for, you know, purposes. The Lascaux replicas are some sort of dioramas. A diorama usually has a distinct educational purpose, it tries to show us something we otherwise wouldn’t be able to see.

Caves are also very real. The caves themselves are not simulating other caves. The decorations, or interior design, do seem to simulate nature in a lot of cases, and can have an undeniable immersive effect. The big Lascaux hall with its ceiling of life-sized running animals might be a bit diorama-like, though it doesn’t represent a ‘real’ situation. Dioramas connecting to prehistoric natural architecture seems to lead to a conceptual dead end (or does it?).

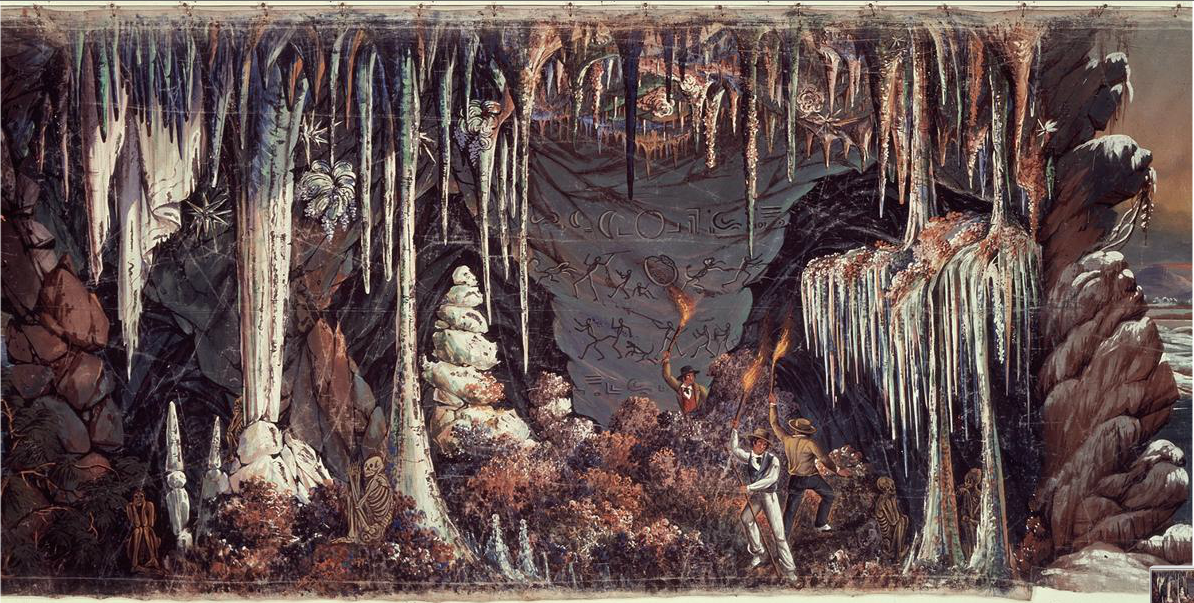

Theatre decors, film sets, and elaborate altars

Caves are natural architecture, and I wouldn’t be surprised if they were the blueprint for all following human-made buildings. Altars, especially the baroque altars, but also stage design, and theatre and movie sets have a much more diorama-like presence. Altars are symbolic dioramas, representing not elements from reality, but visualize a way to get closer to god, or gods, or the afterlife, or enlightenment, or redemption. But they were also used, at least some parts of altars would get meddled with while performing rituals.

Decors and sets only really are dioramas when they’re not in use. Once a play is being carried out on the stage, a set looses its frozen-in-timeness, and becomes part of a time based narrative. Actors interact with the decor, and the diorama is lost. When abandoned, a theatre decor could very well be a diorama, albeit a handicapped one, since it’s missing its context of story and actors. Can a decor on a stage be a diorama in its own right?