The title of this post references two texts accompanying two recent museum exhibitions on the diorama in relation to contemporary art: ‘Exposer l’Absence’, the curatorial introduction of the extensive catalogue for the exhibition ‘Dioramas’ at Palais De Tokyo in Paris in 2017, and the curatorial text for ‘Smaller Worlds. The Diorama in Contemporary Art’ in the Ludwig Museum in Budapest, on view between October 2022 and February 2023, which included one of my works, ‘The White Hide [v]’.

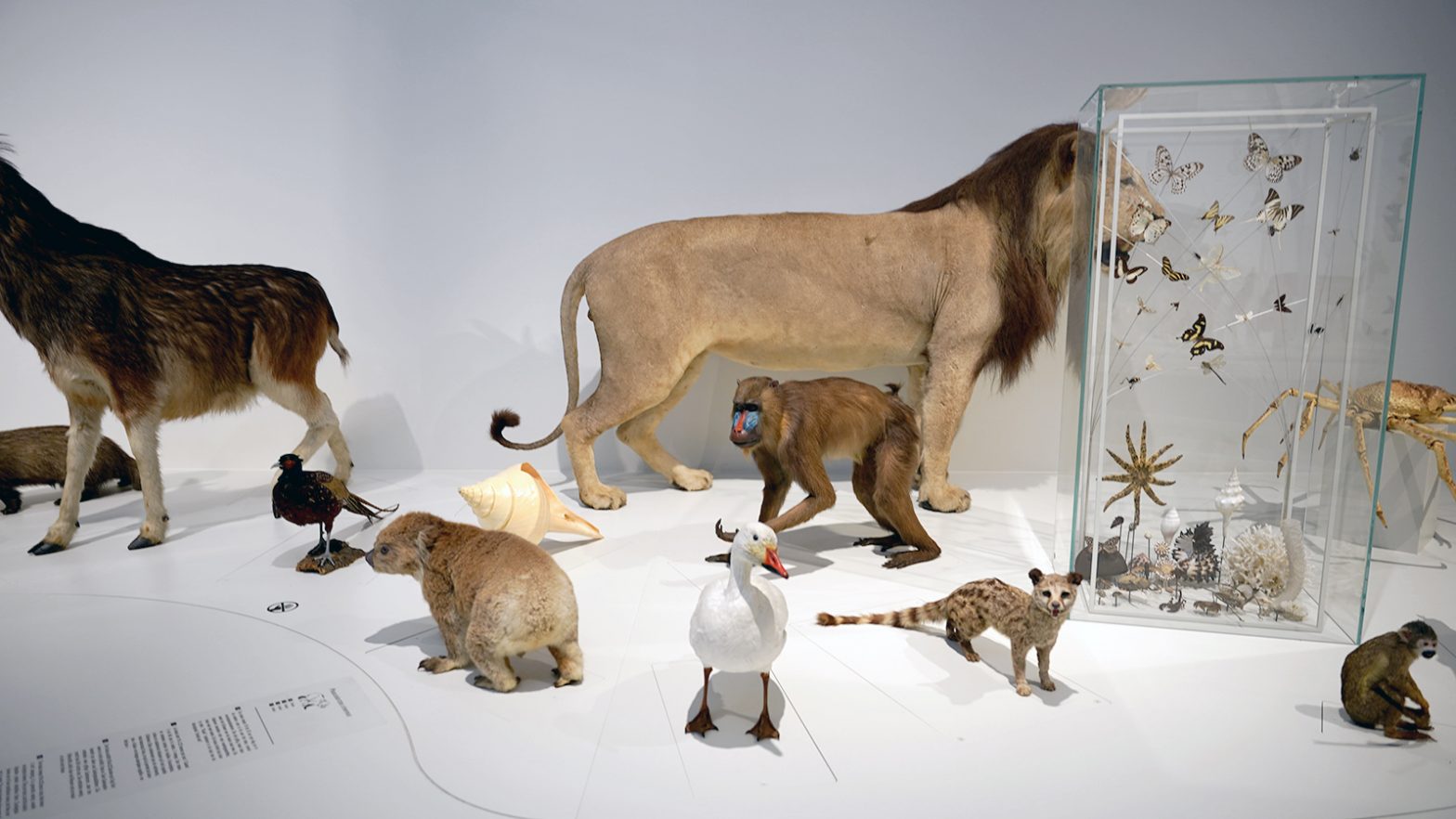

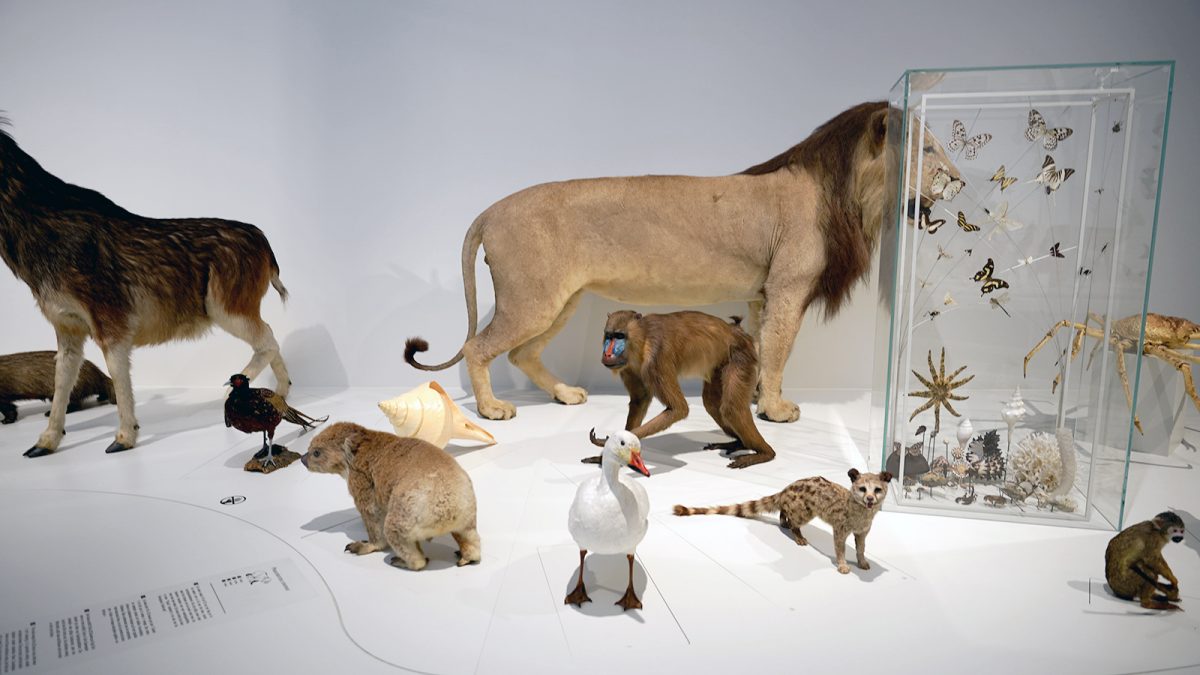

Between June 14 and September 10, 2017, the exhibition ‘Dioramas’ was on view at Palais De Tokyo. This co-production with the Schirn Kunsthalle in Frankfurt shone a light on the particular position of the diorama in art history: “Dioramas goes beyond the historical narrative of the diorama and its influence on major artists of the 20th and 21st centuries. Inviting the audience to step into the hidden mechanisms of a diorama, the exhibition dismantles its strategies of illusionism and allows the viewer to build a critical approach on the power of representation.”1

At the time, I was preparing a solo exhibition at the now discontinued gallery LhGWR in The Hague (The Netherlands), and working on a digital animation loop, ‘The_Archive’. While producing this film, I didn’t realise yet the work was closely related to dioramas, and I failed to see a connection to the Paris exhibition. I didn’t visit ‘Dioramas’, but once I recognized much of my body of work is, in fact, ‘dioramic’, and that the diorama in relation to my digital practice was in need of further investigation – through this doctoral artistic trajectory – I ordered the accompanying publication.

The catalogue not only gives an overview of the works in the exhibition, but also contains a wealth of essays on the subject from historical, conceptual, artistic, and anthropological points of view by the likes of art historian Aleth Mandula, media historian Erkki Huhtamo, historian of science Karen Wonders, philosopher of science Donna Haraway and artist Hiroshi Sugimoto.

The introduction, written by curators Claire Garnier, Laurent Le Bon and Florence Ostende of Palais De Tokyo, and Katharina Dohm of Schirn Kunsthalle, articulates the ambiguity of the diorama wonderfully. It bridges contemporary art – the domain I, as an artist, am part of and participating in – and research on the diorama as a scientific and illusionary manifestation.

‘Smaller Worlds. Dioramas and Contemporary Art’ was conceived by curator and art historian Zsuzska Pétro for the Ludwig Museum of Budapest in Hungary. Pétro departed from an ongoing personal fascination with dioramas. The exhibition was postponed for more than a year due to pandemic restrictions across Europe, and eventually produced by Pétro – from a distance, in Berlin – and curator Jan Elantkowski in the short time-span of six months and in challenging circumstances, forcing the museum to opt for a digital catalogue instead of a printed one.

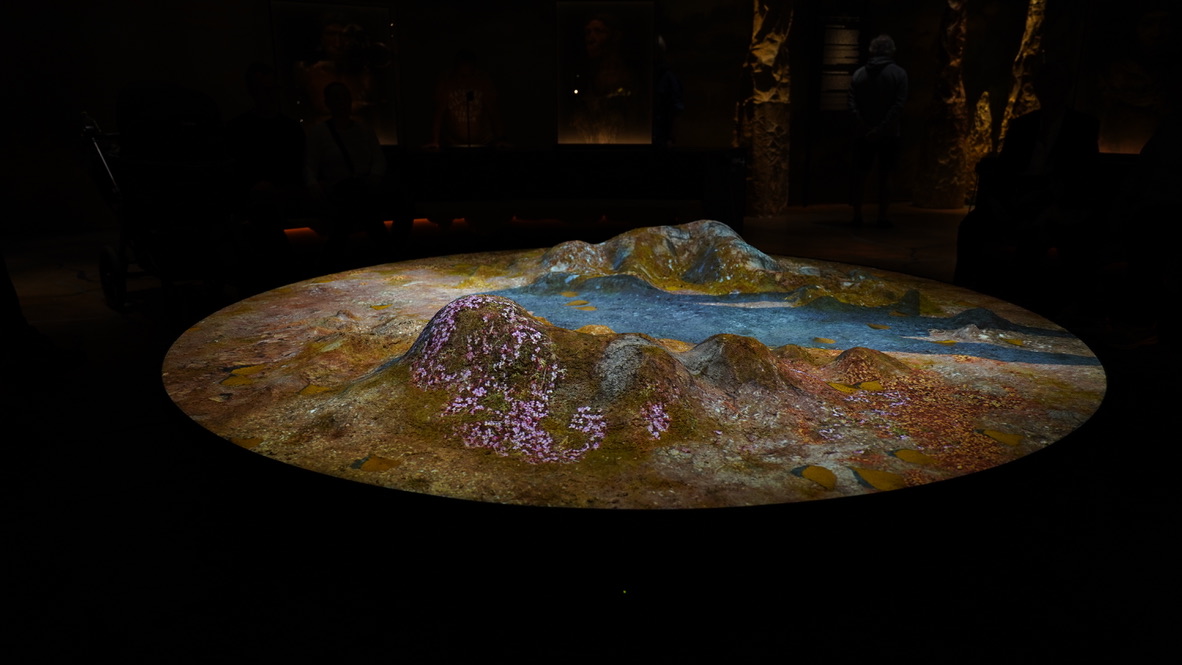

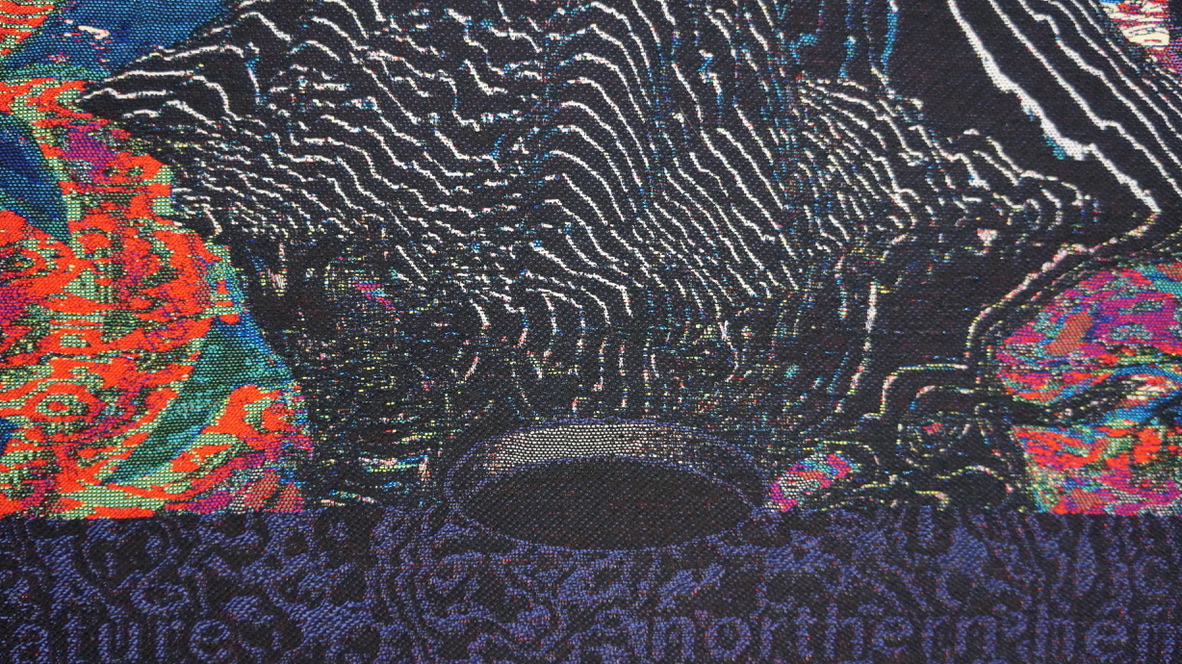

As the title suggests, in ‘Smaller Worlds’ the miniature was prominently featured in lightboxes, installations and sculpture, next to video and animation (by Nathalie Djurberg and Hans Berg, and myself) and works that use Virtual Reality. The exhibition as a whole took place on the museum’s first floor, with atmospheric lighting adding to a sense that the whole floor was a large, dioramic peepbox.

In his opening speech, film director, poet, and cultural attaché of the Hungarian Embassy in Germany, Can Togay dives into the magical effect dioramic scenes often have on the spectator.2 In psychology, ‘affect’ is the emotional response to an experience, literally meaning feeling. In the diorama-experience, Togay emphasizes the ‘sense of wonder’ which also emerges in the eye-witness account of Daguerre’s London diorama by J. Saunders.

There seems to be no better way to survey the multitude of views on the diorama than by means of an extensively supplemented summary of the texts that accompanied both exhibitions, ‘Dioramas: Exposer l’Absence?’ from the Palais De Tokyo exhibition, and the curatorial text by Pétro and Elantkowski and the opening speech of Togay for ‘Smaller Worlds’ in Museum Ludwig.3

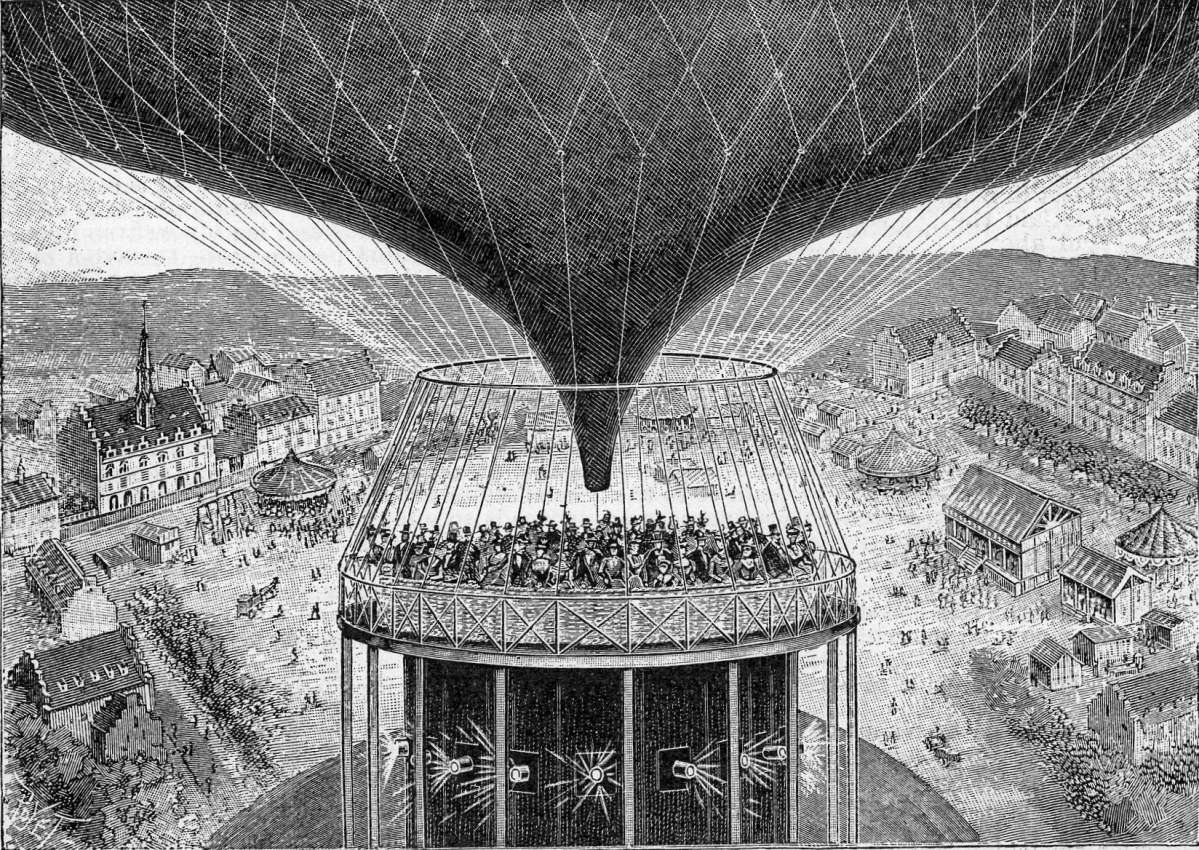

Architecture as technology

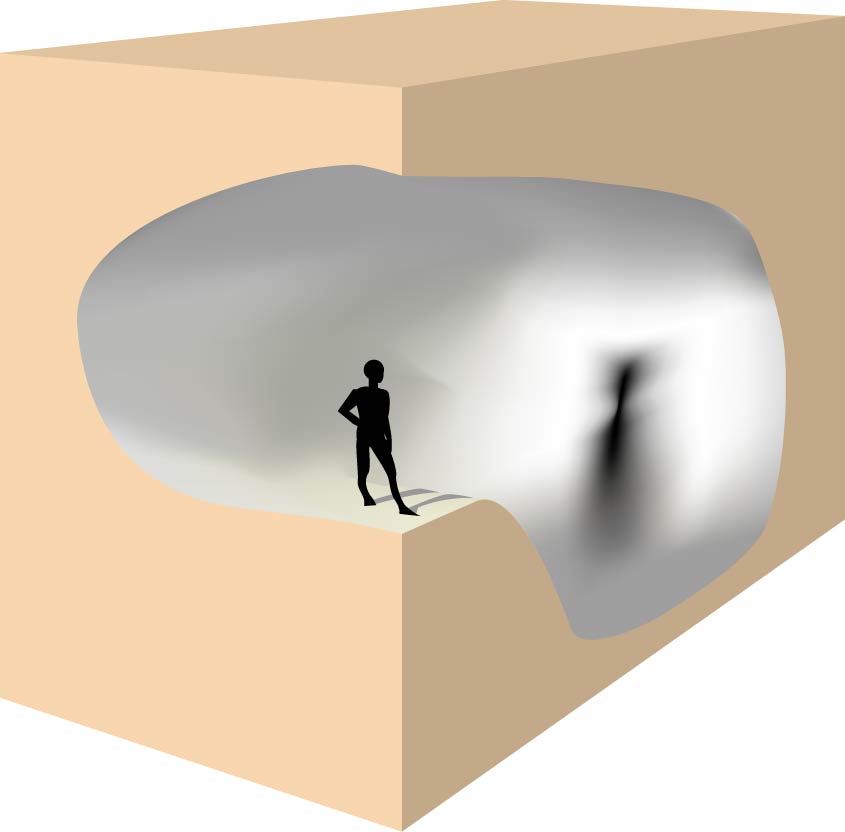

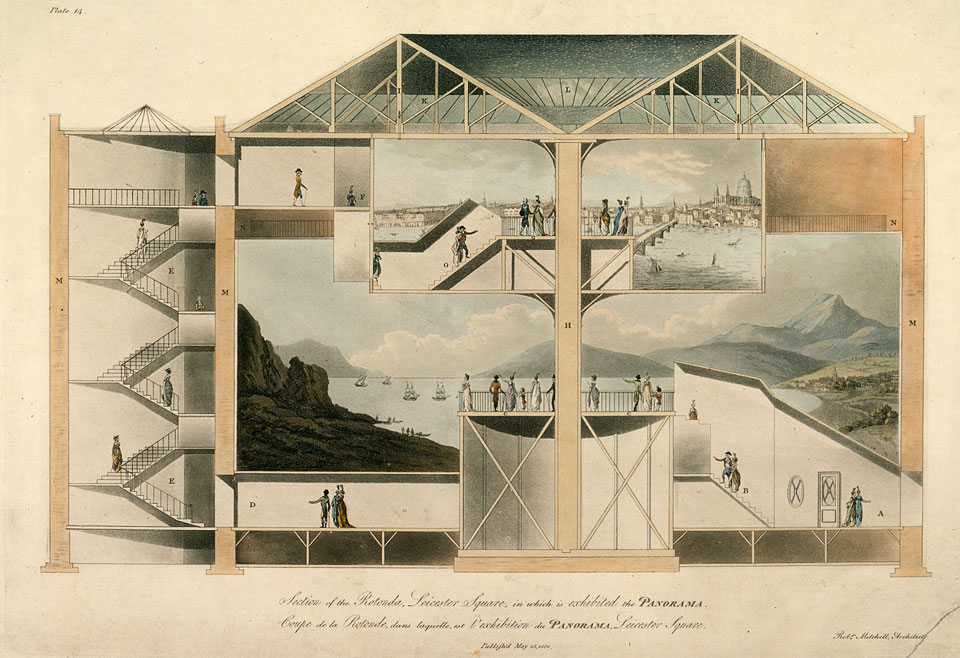

One of the difficulties of describing the diorama, whether it’s Daguerre’s ‘moving painting’ or the habitat dioramas in museums for natural history across the world, is its interrelation to architecture. A diorama is not just the visible scene, but extends to the space that surrounds the depicted ‘view’. Daguerre’s ‘moving paintings show’ needed a specially designed building containing rotating tribunes, and pulleys and levers. The advanced life-sized ‘view boxes’ of natural history museums function best when architectural conditions, such as curved walls and glass panels, are applied.

This relates to what media historian, urban historian and cultural critic Norman M. Klein calls ‘scripted spaces’ in his elaborate – and at times, in the spirit of the subject, purposely disorienting – survey on visual illusions ‘The Vatican to Vegas. A history of Special Effects’ (The New Press, 2004). Klein deconstructs the architecture of Baroque altars, shopping malls, theme parks and museums, but also cinema, sculptures, and paintings by exposing the mechanisms behind the ‘illusion’ in the function of storytelling.

Like Donna Haraway, who considers the museum as “a visual technology”4 and Karen Wonders5, whose elaborate studies on dioramas discuss in detail the many models and technical plans that were part of building a diorama, Klein frequently connects technology to these scripted spaces, for instance when he writes: “And like our disaster movies, Baroque effects relied on “software” of a kind: solid geometry for architecture, optics, sculpture, paint, theater. Numerous handbooks after 1550 detailed how to build these illusions, including charts for carpenters, and texts by leading architects like Serlio, the painter Fra Andrea Porzzo, designers like Joseph Furttenbach the Elder.”6

Returning to ‘Diorama: Exposer l’Absence’, the authors found that even though the diorama is much used as an inspiration for contemporary artists, it is largely absent from art history. The essay gives three reasons that may have contributed to this omission: the rise of modernism, scientific ‘inaccuracy’ and colonialist connotations.

Modernism: the White Cube

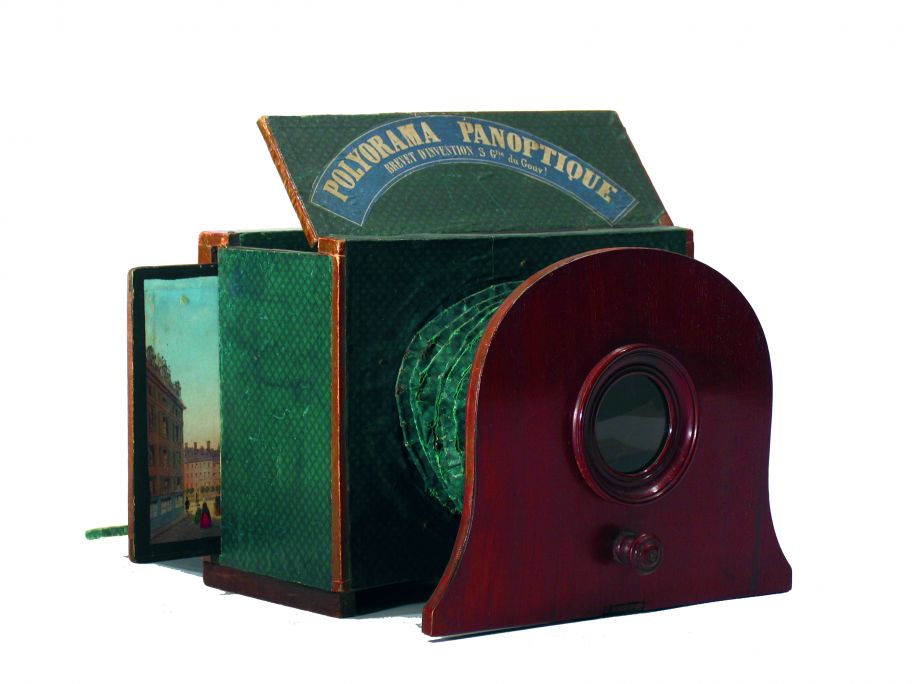

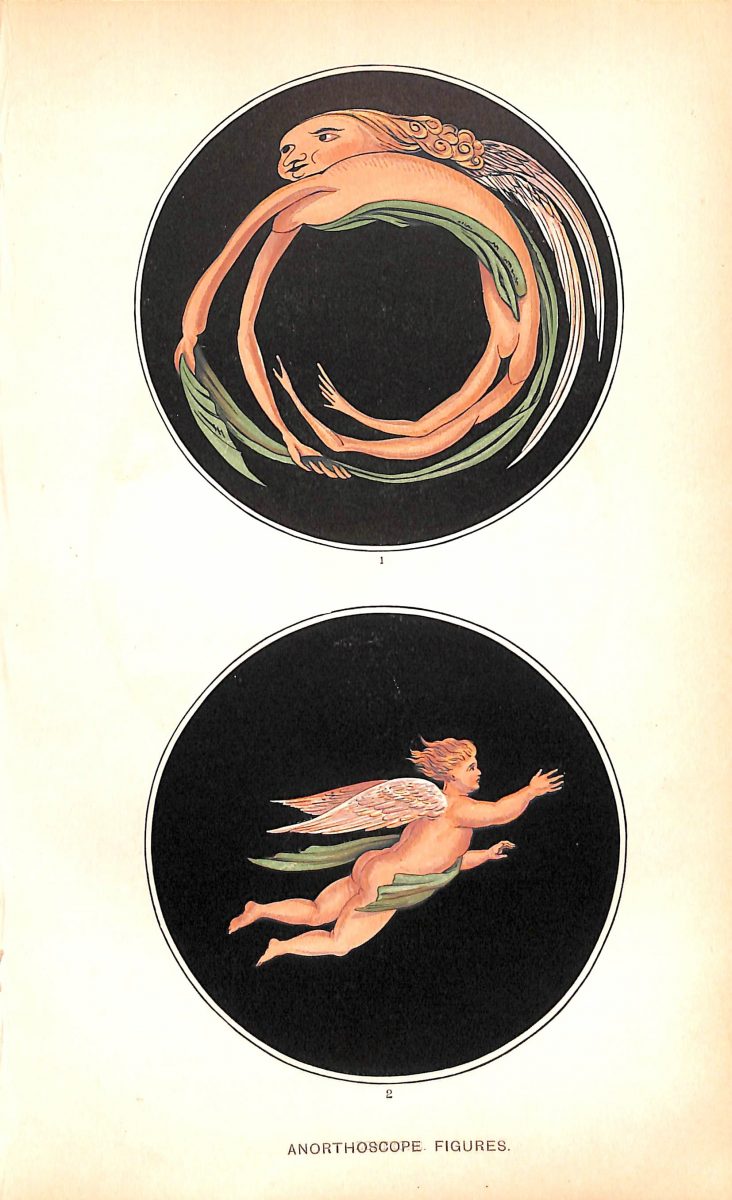

As the diorama was conceived in its multiple forms in the 19th century, 20th century modernism regards ‘illusionism’ as contrary to the essence, the ‘purity’ of art. While visual illusions in the 19th century became increasingly sophisticated and mobile – adding, for instance photography, trick-photography, and stereoscopic images with their specially designed viewers – modernism as a counter-movement rejected the illusionary experience of the pictorial.

Over the course of the 18th and 19th centuries ornamentation lost its symbolic meaning: historical styles were recycled endlessly in neoclassicism, resulting in a mish-mash of revivals with many mass produced objects now labeled as ‘kitsch’ because of their eclectic appearance combining elements from the Gothic, Baroque, and Rococo eras with oriëntalism and exotism, driven by colonialism and upcoming consumerism.

Ornamentation became associated with distraction, a symbol for the faux, fake: the unreal. The functionality of modernism allowed for a return to ‘the real’. In the visual arts it meant a radical departure of the pictorial in favour of the abstract, and the replacement of eclecticism with minimalism.

Museums underwent a similar reconfiguration. Donna Haraway describes the American Museum of Natural History, which opened in 1871: “The building itself presents many visible faces. It is at once a Greek temple, a bank, a scientific research institution, a popular museum, a neoclassical theatre. (…) It is impossible not to feel entering this building that a drama will be enacted inside.”7

Throughout the 20th century, ‘the white cube’ became art’s architecture: a presumed ‘neutral’ space, meant to give room to the individual artwork as opposed to the crowded salons of before, walls covered in various colours and wallpapers, the art floor-to-ceiling presented in shiny, golden frames or on elaborately decorated marble columns. In that context, it’s easy to imagine the diorama as a relic from a dusty, overcrowded, and soot-covered era, at odds with the bright ‘freshness’ of contemporary exhibition design.

Modern – and modernist – museums, however, are subject to their own illusionary mechanisms.

Note: this needs some elaboration.

Virtual architecture: looking both at and through the screen

A way to work around the imposing white cube is the ‘black box’, which will take us from cinema to the presentation of video art, one of the domains my work is taking place in through means of digital animation. In addition to physical exhibition locations, the screen – through the internet – has become a new kind of ‘stage’ for the presentation of (digital) art expressions, even more so since the Covid-19 pandemic restrictions between 2020 and 2022 saw exhibition spaces closed.

The glass covering the computer– and mobile device screens facilitates, in some ways, a new diorama-like experience, especially when it comes to relatively recent applications such as Virtual Reality (VR) and in particular Augmented Reality (AR). Whereas VR provides immersion in an entirely digital environment that requires a helmet disconnecting the senses from the physical world, AR gives the illusion of ‘looking through’ the mobile device screen, overlaying reality with an additional digital layer. This can simply be information, but also digital sculptures that the spectator can walk around or through.

The similarities between digital representations and dioramas has set a reappreciation in motion. We’ll return to this synchronisation of emerging ‘illusionary’ technology and contemporary art through artists such as Eva l’Hoest (‘Under Automata’, 2016), Kelly Richardson (‘Talisman II’, 2021), Auriea Harvey (Minoriea, 2021), and myself (focusing on a series of works pertaining to ‘The Plot’, 2019-2023).

Scientific objections: the Chambers of Horrors

Science came to reject the ‘imprecision’ of the depicted combined species in a natural history setting: the diorama is often perceived to prefer theatre over science, clouding the objectivity of scientific research.

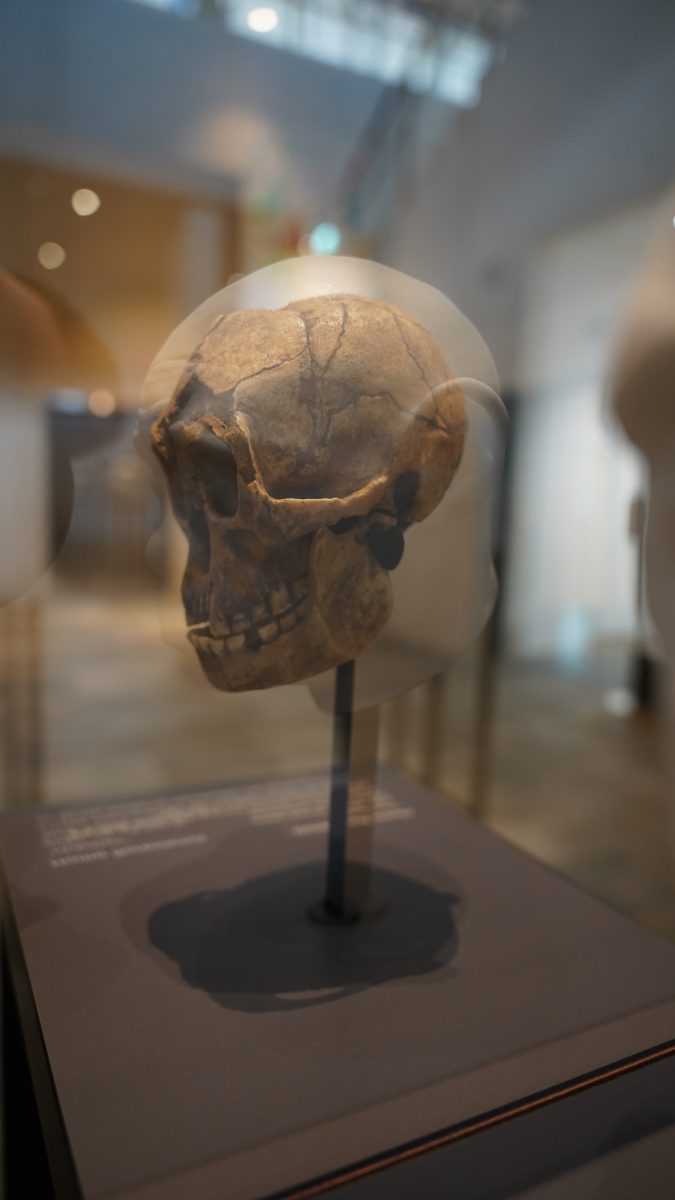

In the chapter ‘Science, Art, and Authenticity in Natural History Displays’ by Lynn K. Nyhart, professor of the history of science at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, as part of the aforementioned ‘Models. The Third Dimension of Science’, three variations of natural history displays are mentioned: mounted animals, habitat groups, and the diorama. The difference between habitat groups and dioramas can roughly be found in the lack of a background painting. Habitat groups are assemblies of mounted animals that are contextually related and often placed in a fragment of simulated landscape. The groups resemble elaborate sculptures that one can study from all angles, rather than the framed, transportive illusion of the diorama.

Nyhart writes: “These naturalistic representations are unlike most other models in science. Models of planetary motion, atomic structure, or DNA, for example, aim to render visible that which we cannot see; a natural history display usually depicts something we already recognize as an animal, a plant, or a section of a landscape. Nor do natural history groups displays resemble physical embodiments of abstract ideas or theories, such as models of mathematics or economies.”8

Science made accessible

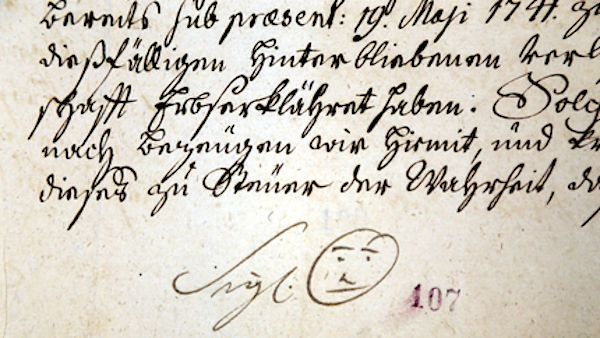

Here perhaps, Linnaean taxonomy needs to be mentioned briefly, as it is this classification ‘model’ the habitat diorama attempts to escape. In 1735, botanist, zoologist and physist Carl Linnaeus published ‘Systema Naturae’, in which he proposed a hierarchical structuring of three kingdoms, the Animal, Vegetable, and Mineral, that in turn were divided in classes, orders, genera, and species.The foundations of this ‘binomial nomenclature’ are still in use, though many changes and additions have occurred throughout time – for instance, a species that, based on its appearance, was first thought to be part of one genera, turned out to be home at another on a genetical level. ((Unfortunately, Linnaeus’ increased his categorization for humans over the course of the Systema Naturae editions, which laid out erroneous groundwork for scientific racism.))

Linnaean taxonomy lies at the base of many natural history displays, comprehensively showing variations and relations amongst species. At the same time, this orderly presentation of specimens – in isolation, mounted in glass cases – poses its own limitations, to which the habitat group and the habitat diorama provide a solution.

Nyhart describes the tension between the scientific representation through Linnaean taxonomy and habitat dioramas as part of a major shift taking place in the early 20th century when museums transformed from scientific research institutions to pass-throughs for knowledge to wider audiences: science made accessible.

She highlights a dispute from the first decade of the 20th century about the display of a habitat group between two German museum directors: Otto Lehman of the Aitonean Museum (near Hamburg) – an admirer of the diorama – and Benno Wandolleck of the Zoologischer Museum in Berlin and later the Ethnographic Museum of Dresden, who compared the display to the ‘panopticon’. Here, I have to note that Nyhart translates the German ‘panoptikum’ – which are waxwork displays such as the popular Madame Tussauds franchise – to the English ‘panopticon’ – which is a term used for a type of prison design aimed at the optimal surveillance of the prisoners. In this context, though, Nyhart’s ‘panopticons’ of course are the waxwork displays.

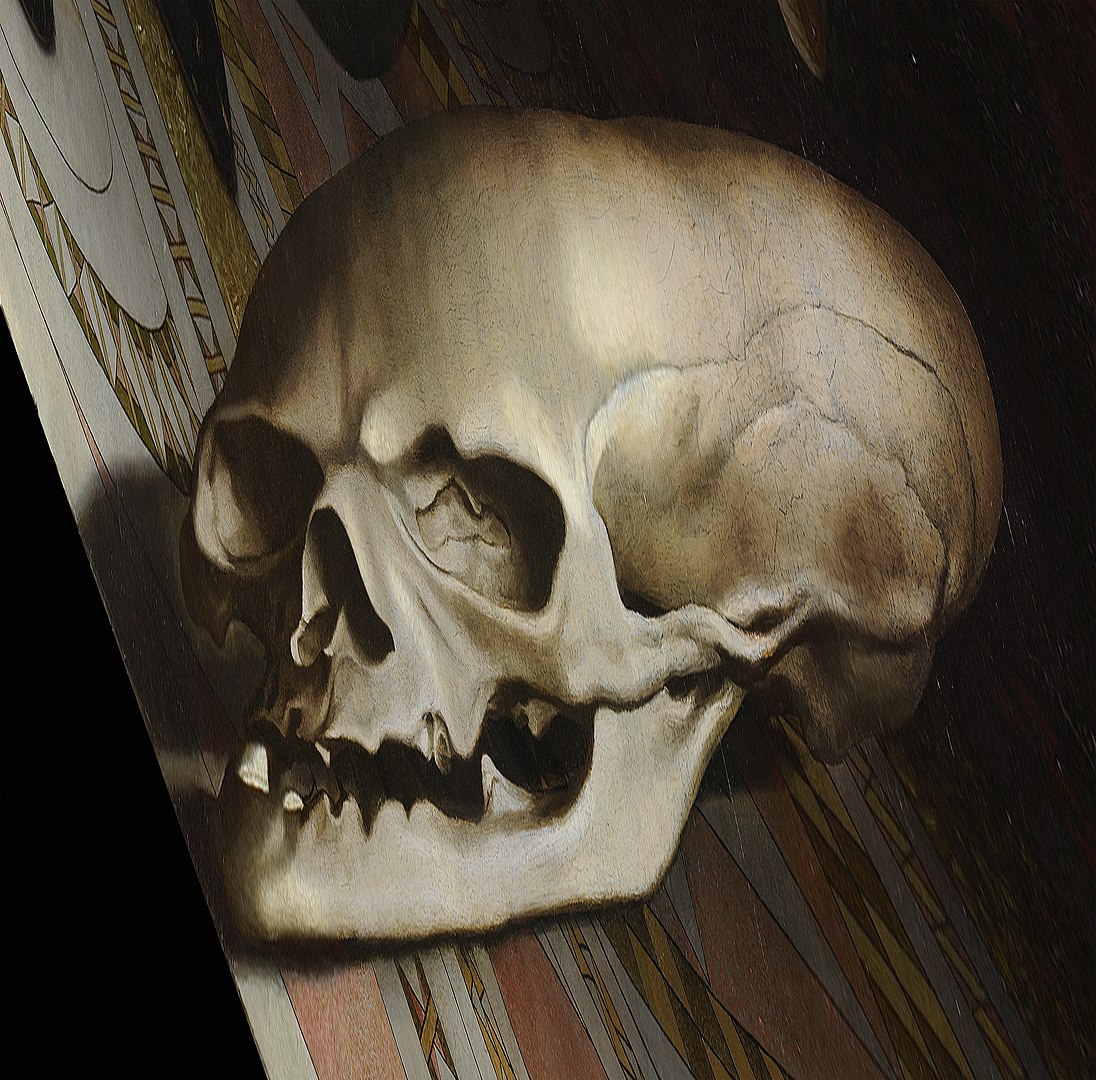

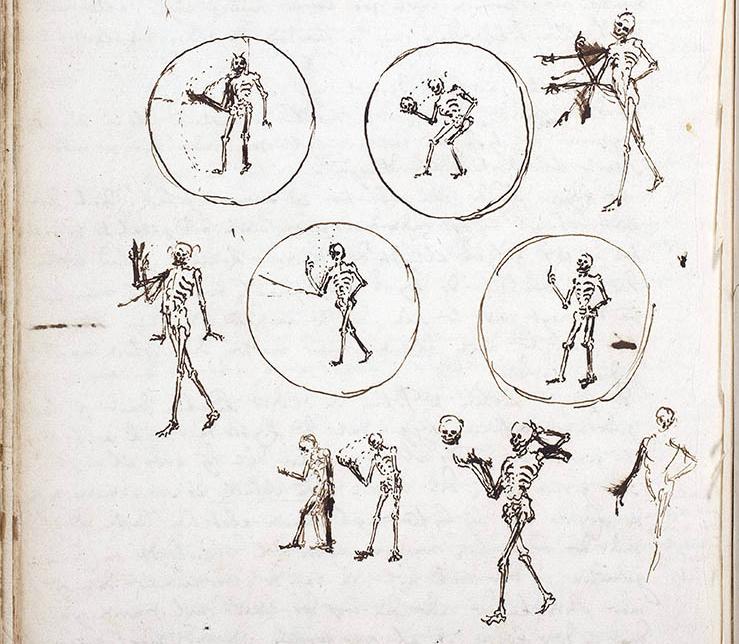

Whereas Madame Tussauds – founded by wax modeler Marie Tussaud in London in 1835 – shows life-like figures of famous people and historical figures, Wandolleck’s objections focused on the wax museum sub-genre of the ‘Chamber of Horrors’: “Emil Eduard Hammer’s three-storey (panopticon) in Munich, for example, offered such gruesome exhibits as “Buried alive” (Lebendig begraben), showing a horrified, long-haired, kohl-eyed maiden pushing off the lid of a coffin; a “Gorilla carrying off a farmer’s daughter”; a polar bear attacking an underclad woman in the act of hanging herself inside a bear-pit; and a piece titled “Nightmare”, showing a small ape leering at an unconscious lace-garbed woman while perched on her stomach.”9

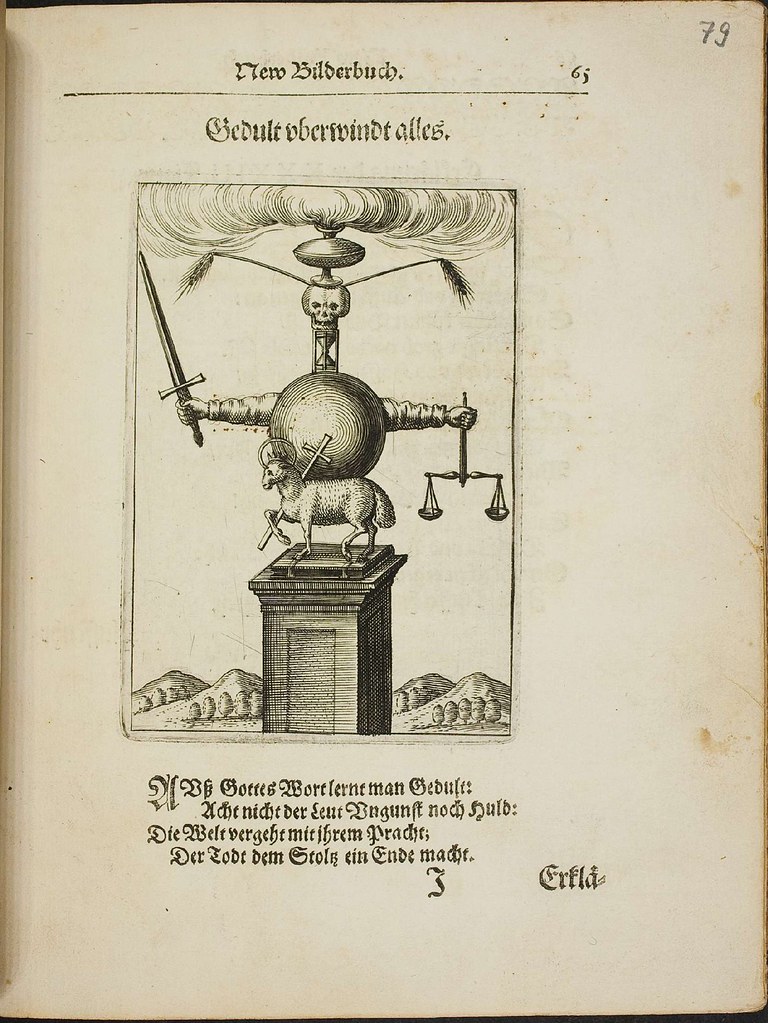

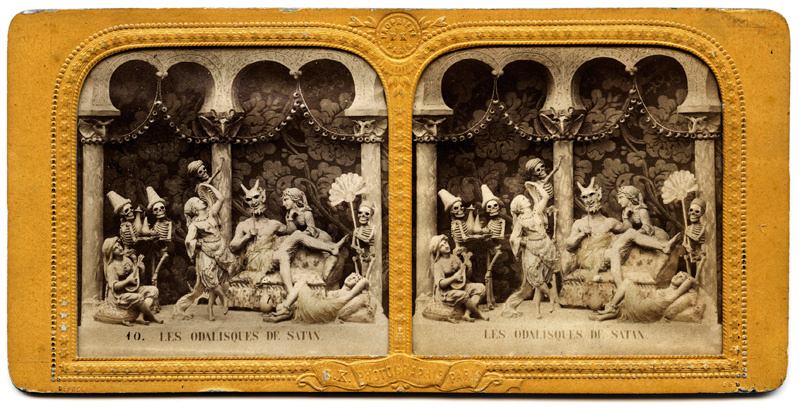

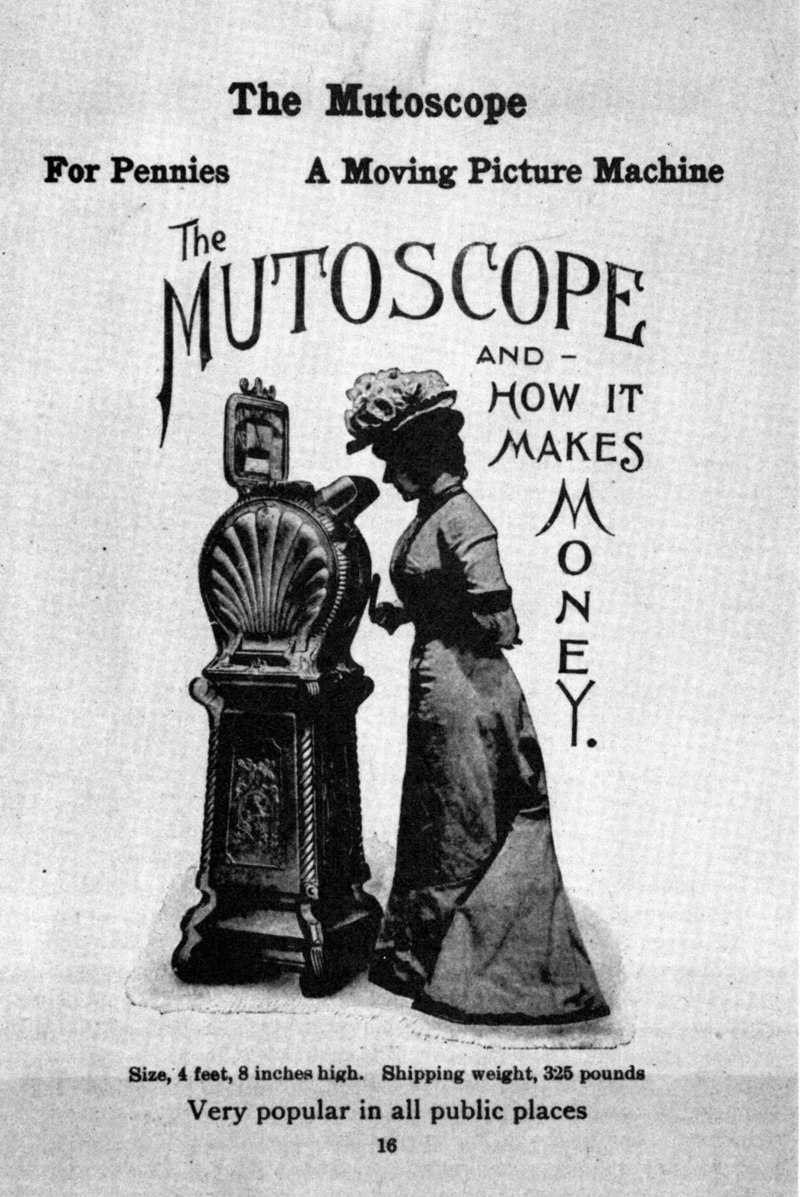

The 19th century popularity of eccentric depictions of skewed historical events and fantasy scenarios extended to an exhausting variety of portable entertainment devices, such as peep shows (viewing boxes, sometimes made of paper that could be folded out), diableries (stereoscopic 3d images featuring dancing skeletons, inspired on the Medieval danse macabre), and dark fairy tales told through magic lantern projections.

In the curatorial text for ‘Smaller Worlds. Diorama in Contemporary Art’ these are described as: “Here, the mischievous thrill of voyeurism meets other-world-ly mystery and the absolute control over this fantasy world. With their secrecy and obscurity, peep shows were able to show the unspeakable and undepictable, hence becoming the form of expression for grotesque and horroristic fiction over time.”

Can Togay, in his opening speech for the exhibition, quotes the protagonist in the opening chapter of Herman Hesse’s novel ‘Steppenwolf”:

“In one of the quietest and oldest quarters of the city, he suddenly catches sight of a small gate with a pointed arch. He stops and takes a good look. Then he sees a patch of soft light above the gate, with colourful letters flickering… He manages to make out a few words:

Magic theatre

Not for anyone

– Not for anyone!

He tries to open the gate, but the heavy old handle won’t let go, no matter how hard he pulls. He backs away. When he steps out onto the pavement again, a few coloured letters of light spill onto the gleaming asphalt. He reads them:

For f-o-o-l-s only!

He moves on, shivering and longing for a magic theatre that only opens its doors to the insane.”

With Daguerre’s Diorama explicitly part of the entertainment industry and the habitat displays sharing the same name and some of its illusionary qualities, it’s understandable there was a need to distinct both types.

Lehman, as an advocate of scientific exhibits of animals, of course distanced himself from the “imbecilic (panopticon) that only satisfies sensual pleasures”.

In 1903, at a conference on ‘Museums as sites of popular education, Lehman presentented his views on the function of his Altonean museum for natural history, history, and folklore: “It is not the intention simply to convey a certain quantity of facts, but to educate the museum’s visitors into thinking humans; they should become accustomed to observing, in order to understand nature.”

Lehman was influenced by the development of the philosophy of perception in educational psychology reflected in the German concept of Anschauung: “an intuited sense of the world mediated through vision.”

In the case of Lehman’s Altona museum, his exhibition strategy resulted in habitat groups rather than dioramas, but the argument is similar. In 1906 and 1907, Wandolleck repeatedly accused Lehman of sacrificing science for drama. Using the Altonean museum display showing a wolf attack on elks he argued that if a scene would be true, it had to have been observed. Since both elk and wild wolves were extinct at the time, disappearing with much of the primaeval forests in Germany in the 18th and 19th centuries, the scene was a mere product of the imagination.

(Insert: the prehistoric life diorama at AMNH? The diorama as a time-machine)

Oppositely, Lehman rejected Wandolleck’s clear distinction between “scientific truth and artistic imagination.” Lehman sought to capture something more than an accurate representation; he was looking to provide an ‘authentic’ experience for the viewer. But what is ‘authenticity’ in relation to a simulation?

Nyhart uses a large coral reef diorama in the Oceanography Museum of Berlin to explore this question: “Here we see how the products of artifice – in this case background paintings – served to reinforce two aspects of authenticity. The scientists’ claim that the scene is the ‘real thing’, strengthened by visual references to specific locations, was brought together with the feeling that was intended to be experienced by the visitor, that the scene looked and felt emotionally like ‘the real thing’”.10

Nyhart writes: “Authenticity (…) involved at once the scientist’s authority in saying something was true and accurate, the preparator’s or artist’s skill in reproducing and provoking that truth, and the viewer’s intuitive experience of the scene as true. Naturalists (…) held fast to the belief that the experience of authenticity required contact with at least a remnant of an ‘original thing’ in the display. Ultimately, that conviction (…) is what has given the natural history group display its immense and long-lasting power.”11

But, as Nyhart notes, the still unresolved tension between scientific accuracy (science) and imaginative representation (fiction) has a political dimension, too: “(…) whose interests, ultimately, was the museum to serve – the scientist’s or the visitor’s? Whose truths should be striven for?” ((Nyhart, Natural history displays, Models. The Third Dimension of Science, p. 325.))

Colonialist connotations: The Diorama Dilemma

Circling back to the introduction essay for the 2017 Dioramas exhibition, ‘Exposer l’Absence’, the third reason for the absence of the diorama in an art historian context is the ambiguous ‘morality’ that comes with the habitat diorama’s colonial connotations that, over time, seemed best to be avoided. This, in itself, is a web of contradictions and, in the case of museums across the globe – of natural history, art history, ethnography, and contemporary art alike – has throughout the last few decades increasingly become an ongoing reinvestigation of collections and displays.

A polyphony of stories that does not harmonize: Donna Haraway’s The Teddy Bear Patriarchy

Between the late 1800s and 1930, the largest concentration of habitat dioramas was found in Sweden and in the US. This is explained by Wonders “(…) by the fact that unspoilt landscape and wildlife were more plentiful in Scandinavia than elsewhere in Europe, and had become a major parameter of national identity; as pristine wilderness was vanishing under the onslaught of industrial progress, biological exhibitions of specific, regional habitats functioned as archives of cultural riches.”

Wonders continues: “The same was true for the US. The national identity of the US has always been closely associated with the magnificence and vastness of its wilderness regions and with the seemingly unlimited amount of wild game inhabiting these. To recreate wild animals—both birds and mammals—and their natural environment in the museum, meant preserving a major part of the national heritage.”12.

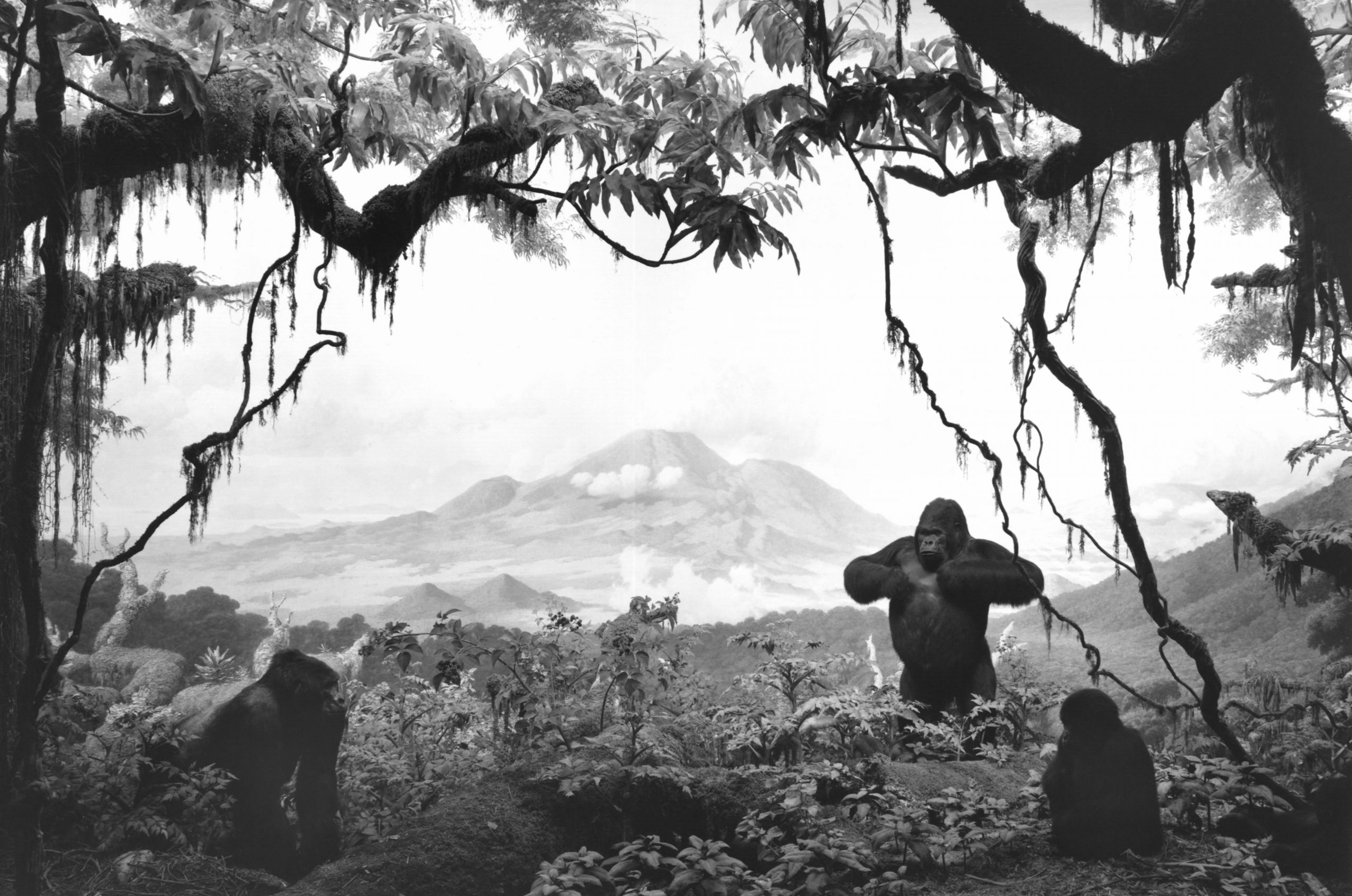

“There’s a polyphony of stories, and they do not harmonize.”, as Donna Haraway puts it in her 1984 essay ‘The Teddy Bear Patriarchy: Taxidermy in the Garden of Eden, 1908-36’. In this essay, Haraway thoroughly deconstructs the dioramas in the Akeley Hall of African Mammals in the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH, in short) in New York, and the Theodore Roosevelt Memorial in the same museum.

A central figure in the text is Carl Akeley (1864-1926), who is known to have created the first habitat diorama for a science museum, the Milwaukee Public Museum, in 1889. He went on to design the Akeley Hall of African Mammals in the American Museum of Natural History in New York, where he became the founder of the AMNH exhibitions lab. The AMNH is internationally recognised for its immense amount of dioramas of a stunning illusionary quality.13

Akeley was a conservationist and a hunter, a combination that was, and still is, frequent and returns in the chapter ‘Himalaya at Dawn’ through the person of the British major Percy Powell-Cotton, of who is “noted for bringing an extraordinary number of animal specimens back from his travels across Africa, potentially creating the largest collection of game ever shot by one man.”14

Akeley, too, shot many of the animals for his displays himself, most notably the silverback gorilla ‘The Giant of Karisimbi’.

Haraway uses the figure of Akeley and his entourage – which includes his wife Mary Jobe Akeley, who was an explorer in her own right and wrote many of his books – and the dioramas in the Hall to take a critical look at the dynamics of colonialism, racism, white supremacy and patriarchal dynamics in the fields of science.

Akeley was also a photographer and filmmaker, inventing a new type of movable camera that could be wielded in barely accessible natural environments in order to ‘visually’ collect animals for scientific research. Using the killing of the gorilla group in central Congo (now Zaïre), Haraway connects the hunting rifle (through the vision of “man, the hunter”) to the camera lens; not just the lens of the nature photographer, but also of the visitor in the AMNH that takes a snapshot of a diorama.

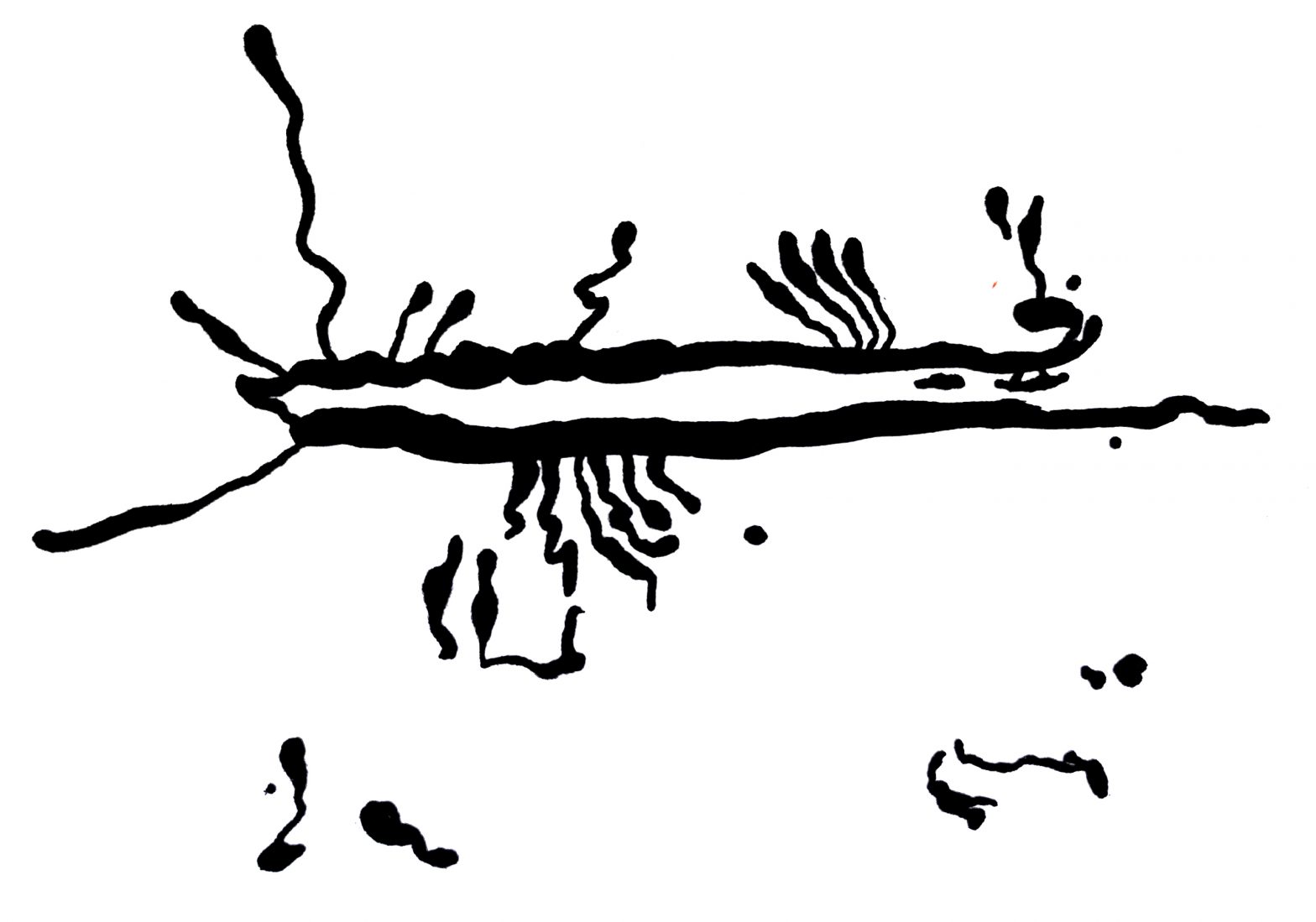

The hunting of the gorilla group near the Virunga volcano in 1921 had an existential impact on Akeley, causing him to persuade the Belgian king Albert II to turn the area into the first African National Park, modeled after the national parks of the United States. Haraway reconstructs Akeley’s very first encounter with the notoriously elusive gorilla: first, there were the footprints – traces that look like handprints in the mud – and within minutes of its first sight, Akeley had killed him.

This haste perhaps was fuelled by the news that the prince of Sweden had recently shot 14 gorillas, and the realisation that “collecting might be very difficult”. Akeley was already very much aware that a supply of gorillas wasn’t infinite.

By the 1880s, the North American continent was entirely colonised (“the closing of the Western frontier”), resulting in the near extinction of bison and the complete extinction of the passenger pigeon in 1914. The publication ‘Windows on Nature’ (2006), issued by the AMNH and focusing on the history and construction of the dioramas in the museum, notes: “Entire populations of waterfowl and shorebirds had been wiped out by intense and unregulated commercial hunting. Big game animals such as deer, moose, bears, elks, and antelope shared similar fates, as no regulations were in place governing when they could or could not be hunted. The millinery (hat-making) trade annually killed hundreds of thousands of nesting egrets, terns, herons, and other bird species for their beautiful nuptial plumes. Scientists and government leaders were spurred to action.”

At the same time, social changes including the start of the emancipation of the working class, took place, and Haraway writes about this: “Akeley and his peers feared the disappearance of their social world in the new immigrations after 1890 and the resulting dissolution of the old imagined hygienic, pre-industrial America. Civilization appeared to be a disease in the form of technological progress and the vast accumulation of wealth … by the very [same] wealthy sportsmen who were trustees of the [AMNH] and the backers of African Hall.”15

A contrast appears between the portraying of the figure of Akeley by Haraway, in 1984, and Quinn in AMNH’s ‘Windows on Nature’ in 2006. Haraway views Akeley as an extension of the colonialist machine, an almost tragic figure locked between the dominant sense of superiority of the Western civilisation and its scientific order, and an utterly romantic longing for finding his place in the natural world.

Quinn celebrates Akeley as a passionate conservationist, an adventurer willing to sacrifice his health – he was mauled by a leopard, and almost fatally attacked by an elephant – for science. Here, Akeley emerges as a real-life Indiana Jones.

Author Maria Golia summarizes Akeley’s position in an essay for the platform Engelsberg Ideas: “Akeley could justifiably claim the title of naturalist; he studied animals in the field, recording his observations, and was instrumental in convincing the government of Belgium-colonised Congo to establish a wildlife park, Africa’s first, to conserve the gorilla habitat. He was nonetheless susceptible to expectations concerning manhood and sportsmanship, whereby killing animals was viewed as a gesture of respect, the facing of a worthy foe.”16

Throughout the 18th, 19th, and early 20th century this duality was common in almost every scientist–explorer: even though he was a reluctant expeditionist, Charles Darwin, too, was an avid hunter, sending home crates with thousands of exotic birds and insects from his Beagle journey. Unsurprisingly, collecting animals for science in some cases caused the extinction of species, in particular on the vulnerable ecosystems of islands. 17

The most controversial, and in current times rightfully fiercely rejected form of ‘natural history’ displays, were of course the inclusion and portrayal of the indigenous people the expeditions encountered.

Notorious are the human zoos, of which the ‘human zoo of Tervuren’ was the last. During the world fair of 1958 in Brussels, 150 people from Belgian Congo – then still a Belgian colony – were ‘exhibited’ in the confinements of an imitation of a Congolese village, and subject to daily abuse of the visitors. Two years later, Congo became independent.

The most extreme example was ‘El Negro’, a Tswana warrior, ‘collected’ and taxidermied in 1843, and who was shown in the Darder museum for natural history in the Spanish town of Banyoles until 1997.18

“As I was on my way to the Human Room, an annex of the Mammal Room, past a climbing wall with apes and the skeleton of a gorilla, my merriment gave way to a shudder. There he was, the stuffed Negro of Banyoles. A spear in his right hand, a shield in his left. Bending slightly, shoulders raised. Half-naked, with just a raffia decoration and a coarse orange loincloth…”, journalist Frank Westerman writes in ‘El Negro and me’ (2016).

“… El Negro turned out to be an adult male, skin and bones, who hardly came up to one’s elbow. He was standing in a glass case in the middle of the carpet.

This was not Madame Tussaud’s. I was not staring at an illusion of authenticity – this black man was neither a cast nor some kind of mummy. He was a human being, displayed like yet another wildlife specimen. History dictated that the taxidermist was a white European and his object a black African. The reverse was unimaginable. I flushed and felt the roots of my hair prickling – simply from a diffuse sense of shame.”

From ‘Windows on Nature’: “By the late 1950s, however, the popularity of the diorama as an exhibit medium was waning. Dioramas required expensive collecting expeditions and were time-consuming to produce. Many of the species they depicted were becoming so endangered in their native habitat that collecting for display was deemed unacceptable.”19

It is of no surprise that against the background of a reckoning with white supremacy, colonialism, the idolisation of “man, the hunter”, and the biodiversity crisis, the habitat diorama lost its luster.

It led to the “diorama dilemma”, as ‘Diorama: Exposer l’Absence’ calls it: museums had to decide whether to restore the historical dioramas in their exhibitions, or to remove them. The dilemma centred on the complex relation between the popularity of the diorama with the public and its unique position in media history, and a ‘disaffection’ that arose from the critical discourse. Eventually, many of the dioramas were removed.

- Exhibition text taken from the website of Palais De Tokyo. https://palaisdetokyo.com/en/exposition/dioramas/ [↩]

- The text of the speech is included in the (digital) catalogue for Smaller Worlds, which can be found on the website of the Ludwig Museum: https://www.ludwigmuseum.hu/system/files/publication/attachments/2023-01/230123_kisebbvilagok_online.pdf [↩]

- Dioramas. Palais De Tokyo, Flammarion, Paris, 2017, p.8 – 13. [↩]

- Donna Haraway, The Teddy Bear Patriarchy, Duke University Press, 1984, p. 34 [↩]

- Karen Wonders, Habitat Dioramas: Illusions of Wilderness in Museums of Natural History. Uppsala: Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis, 1993. [↩]

- Norman M. Klein, The Vatican to Vegas. A History of Special Effects. The New Press, 2004. p. 5 (introduction). [↩]

- Donna Haraway, The Teddy Bear Patriarchy, Duke University Press, 1984, p. 21 [↩]

- Lynn K. Nyhart, Science, Art and Authenticity in Natural History Displays, Models, Stanford University Press, 2004. p. 307 [↩]

- Lynn K. Nyhart, Science, Art and Authenticity in Natural History Displays, Models, Stanford University Press, 2004. p. 313. [↩]

- Nyhart, Natural history displays, Models, p. 325. [↩]

- Nyhart, Natural history displays, Models, p. 331. [↩]

- Wonders. Habitat dioramas as ecological theatre, p291-292 [↩]

- Quinn, Windows on Nature, Abrams/AMNH, 2006, p. 15. [↩]

- A quote from Powell-Cotton’s Wikipedia page, reference: The Companion Guide to Kent & Sussex, 1999. [↩]

- Donna Haraway, The Teddy Bear Patriarchy, Duke University Press, 1984, p _ [↩]

- Maria Golia, Carl Akeley – the contradictory life of a taxidermist and hunter turned wildlife photographer, published September 16, 2021 on Engelsberg Ideas. https://engelsbergideas.com/portraits/carl-akeley-the-contradictory-life-of-a-taxidermist-and-hunter-turned-wildlife-photographer/ [↩]

- David Quammen, ‘The Song of the Dodo. Island Biogeography in an Age of Extinction’ [↩]

- Frank Westerman. El Negro en ik. [↩]

- Quinn, Windows on Nature, Abrams/AMNH, 2006, p. 21. [↩]